Opening Reflection

For many years, I buried my own unrecognised, mental health struggles. I told myself that if I ignored my pain and my confusion, it would fade with time. None of it did. Instead, all my issues built up behind a mental dam until the pressure became too great and the dam burst.

As an engineer, I believed I could design my way out of the problem, apply logic, find a quick fix, and move on. But the mind is not a machine. You cannot tighten a bolt or swap out a component to make suffering vanish. It takes patience, honesty, and a change in thought process. It takes long, deliberate work to heal. I was using the wrong tools for the job and failing every time.

Our society faces the same challenge. We bury problems, injustice, inequality, crime, poverty, and mental health, as though they will resolve themselves if ignored. We patch over cracks with political gimmicks, soundbites, snappy headlines, and short term fixes, hoping the dam will hold, if we even give the dam a second thought. But the dam never holds in the long term. Sooner or later, the pressure bursts through, and the consequences are far worse than if we had faced the issues openly from the start.

This is the story of the Criminal Justice System in Britain. It is a system that has too often looked for the quick answer, the headline solution, the promise of efficiency without the hard work of reform. And just as with an individual, ignoring the deeper problems has only allowed pressure to build, until the cracks spread across the entire structure. Just as with an individual, if we fail to invest in ourselves, we will fail, not for lack of effort, but because effort without the right tools or mindset achieves nothing.

What follows in this chapter is not just an account of laws, prosecutions, prisons, and probation. It is an examination of what happens when a nation chooses illusion over reality, when it buries its hardest truths rather than facing them. If we are to build a justice system that truly serves the people, we must learn to do what I eventually had to do myself: stop pretending the dam will hold, and start the patient, deliberate work of rebuilding it properly.

The Modern History of the Criminal Justice System

In the history of the Criminal Justice System in England and Wales it has undergone significant development since the establishment of the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) in 1880. The inception of this office marked a shift in the approach toward public prosecution, reflecting a growing recognition of the state’s role in criminal law enforcement. Before this institutional change, prosecution was usually the responsibility of private individuals, which raised concerns about inequality and the effectiveness of legal representation for victims.

The late 19th century was marked by a societal transformation in England and Wales that highlighted the necessity of a more centralised approach to criminal justice.

The private prosecution system emphasised the need for a structured and equitable approach to justice, contributing to the establishment of the DPP in 1880, which aimed to evolve toward a more balanced criminal justice system focused on prosecutorial efficacy and victim support (Rock, 2004) (Wemmers, 2009) (Spencer, 1997).

Institutionalising public prosecution sought to represent the interests of the state while considering the rights and needs of victims, a theme that continued to evolve in subsequent decades. Spencer notes that the victim’s position began to gain momentum; however, historically, victims were relegated to a minimal role, primarily as witnesses in criminal proceedings (Spencer, 1997).

With the turn of the 20th century, further reforms aimed to bolster the effectiveness of public prosecutions. Legislative changes throughout this period, particularly post 1945, mirrored shifts in societal attitudes towards crime and the responsibilities of the state towards victims. The Criminal Justice Act of 1988 is a notable milestone, emphasising the prosecutor’s role and establishing statutory roles to ensure fairness, moving toward a more victim-inclusive framework (Wemmers, 2009) (Doak, 2005).

However, the systemic focus often remained weighted toward the state’s authority, frequently sidelining victims’ active participation in the justice process (Rock, 2004) (Wemmers, 2009) (Doak, 2005).

The latter part of the 20th century into the 21st century witnessed the emergence of the victims’ rights movement, significantly influencing policies within the criminal justice system. Victims began advocating for their rights and participation in the judicial process. The recognition of victims’ rights found legislative expression in the Victims’ Code of 2006, which established entitlements for victims to receive information about their cases and support services (Spencer, 1997) (Stickels & Mobley, 2008).

However, despite these advancements, systemic barriers persist, as the criminal justice process often still positions victims primarily as witnesses rather than integral participants (Doak, 2005) (Wemmers, 2009).

The establishment of the DPP can also be contextualised within broader changes in governance and legal accountability. An accountable prosecutorial body was necessary to fill the void left by individual prosecutions, underscoring the need for a cohesive legal framework (Holder, 2018).

The increasing globalisation and complexity of crime necessitate continual adaptations within the criminal justice system. Issues like cybercrime and international terrorism present challenges requiring coordination across national boundaries, demanding innovative responses from the DPP and the criminal justice framework (Holder, 2018). The institutional responsibilities of the DPP have expanded to address these dynamic challenges, reflecting the need for a multifaceted legal approach to modern crime.

The trajectory of the Criminal Justice System in England and Wales since the establishment of the DPP illustrates a complex evolution from a privatised, victim initiated prosecution system to a more structured public prosecution model.

The gradual integration of victims’ rights and restorative justice approaches highlights ongoing transformations aimed at balancing victims’ and the state’s interests, advocating for a justice system that recognises the importance of collaboration and community engagement in addressing crime (Rock, 2004) (Bouffard et al., 2016) (Wemmers, 2009) (Spencer, 1997) (Stickels & Mobley, 2008).

The Legal Aid System

The legal aid system in the United Kingdom has a complex history, deeply intertwined with the evolution of social justice and state intervention in the realm of law. Its inception can be traced back to the Legal Aid and Advice Act of 1949, which aimed to make legal assistance accessible to economically disadvantaged individuals, thereby integrating legal aid into the welfare state paradigm (Bradley, 2023). The post-World War II context, marked by a societal commitment to equity and social justice, created pressing demands for a structured form of legal support for the underprivileged, especially in civil and criminal matters (Okoro, 2022).

However, over the decades, the legal aid system has faced significant challenges, particularly in terms of funding. The impacts of austerity measures introduced in the wake of the global financial crisis have exacerbated these challenges, with the legal aid system being viewed as a collateral casualty of broader economic policies (Truxal, 2020). The reduction in legal assistance has resulted in a considerable justice gap; many individuals find themselves unable to afford legal representation, which is critical for navigating complex legal systems (Okoro, 2022). Moreover, systemic issues, including cultural and technological barriers, have perpetuated inequalities in access to justice, further complicating the legal landscape in modern Britain (Okoro, 2022) (Hemsworth, 2021).

Reviews have highlighted that legal aid funding has been under strain, particularly since the implementation of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO). This Act resulted in substantial cuts to the legal aid budget, contributing to a situation often described as “discount justice,” where the availability of legal representation has become increasingly limited (Truxal, 2020) (Boylan et al., 2016). Public backlash has been recurrent, manifesting in various advocacy efforts aimed at restoring funding and ensuring that justice remains accessible to all (Boylan et al., 2016).

The changes in the funding and provision of legal aid in the United Kingdom have had significant impacts on the family court system, particularly affecting how non-resident parents achieve justice in family court battles. The introduction of LASPO in April 2013 marked a turning point, not only resulting in drastic cuts to legal aid funding, but decimating funding for family law cases. These restrictions and removal of funding, except in extreme cases of abuse, have led to an increase in self-representation among litigants (Litigants in Person), as many individuals have found themselves navigating the complexities of the family court system without professional legal support.

The introduction of LASPO in 2013 had profound ramifications for justice in the UK, Amnesty International stated in a report that the year before the act was implemented, legal aid was granted in 925,000 cases, the year after, assistance was given in 497,000 cases, a drop of 46%. creating in effect a two‑tier system. Note: this aggregates civil and criminal legal aid certificates granted (“acts of assistance”).

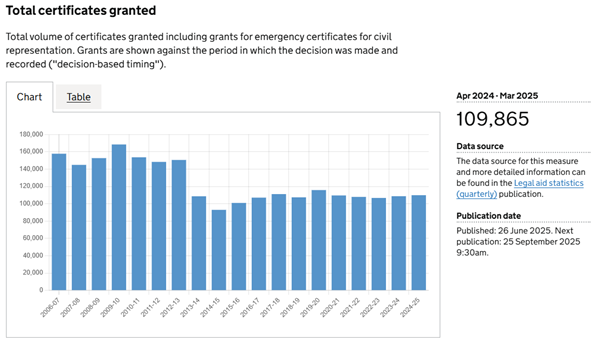

The Ministry of Justice’s own statistics show a parallel contraction within civil representation specifically. The chart below tracks certificates granted for civil representation (including emergency certificates) from 2006 to 2025. Following LASPO (2012–13), annual grants fell from ~ 150k – 170k pre‑LASPO to 109,865 in 2024–25, a sustained decline of about 28–35% that has never been reversed. (Figures are recorded on a “decision‑based timing” basis.)

Ministry of Justice data on total legal aid certificates granted (2006–2025). The sharp decline after 2012–13 illustrates the impact of LASPO, with grants falling from more than 150,000 to just 109,865 in 2024–25.

The ramifications of the lack of legal aid funding are profound for non-resident parents who are not in a financial position to appoint private solicitors, and they often face substantial obstacles when attempting to assert their rights or negotiate arrangements for their children. The surge in self-representation (Litigant in Person or LIP) creates a scenario where non-resident parents may lack the necessary skills to effectively advocate for themselves, leading to imbalances in the court system. Research indicates that many family court proceedings now involve LIPs, which complicates court processes and often results in delays and inefficiencies. The presence of LIPs can contribute to a more punitive legal environment, contrary to the intended therapeutic goals of family court systems.

The average hourly rate for a family lawyer in the UK varies significantly but generally falls within the range of £150 to £300+, with rates increasing based on the lawyer’s experience level and geographic location, particularly in London. For instance, a trainee or junior lawyer might charge around £150-£200 per hour, while experienced solicitors could charge £250-£300 or more, with some senior solicitors in London charging upwards of £500 per hour. The median hourly salary in the UK is £18.64 per hour (ONS 2024), how they are supposed to pay for a lawyer charging more in one hour than they earn in 8 hours (£150), 16 hours (£300) or almost 27 hours in the case of London based senior solicitors. This is unrealistic and unjust. Just reading through the paperwork for a case can cost from £7,000 to £20,000 depending on the complexity and the size of the bundle.

Moreover, the consequential delays and increased backlogs in family court cases have diluted the effectiveness of the legal process, increasingly frustrating parents who are seeking timely resolutions to their disputes. As costs associated with court fees rise, coupled with significant funding cuts, economic barriers further exclude many non-resident parents from accessing justice. This situation has led to a significant decline in the use of mediation, which was advocated as a more amicable resolution method following LASPO. The decline in eligible mediation cases has been stark; for instance, the number of individuals attending initial mediation meetings has dropped by 60%. These trends highlight the broader systemic issues that stem from inadequate funding and policy decisions surrounding legal aid.

Additionally, the perceived inequity extends beyond economic constraints; non-resident parents often encounter biases within the family court system. Research and campaign groups have argued that outdated biases and judicial attitudes often favour resident parents, who are usually the mothers, and thus undermining non-resident parent’s claims, usually the fathers. This dynamic calls into question the fairness and transformative potential of the family court system, particularly in light of modern legal aid frameworks that prioritise cost saving over equitable access.

The changes wrought by funding cuts to legal aid have significantly impacted the family court system, making it increasingly challenging for non-resident parents to achieve justice. The shift to self-representation, coupled with rising costs and systemic biases, underscore the urgent need for reform in the funding and provision of family legal aid to restore equity and fairness in family law proceedings.

Here is a quote from The Guardian on a report published in 2017,

One consequence has been that separating couples are not evenly represented. One woman told Amnesty: “When I go to court, I have to cross-examine my ex. That terrifies me. I have so many sleepless nights. If I lose, I know I will blame myself – it’s because I wasn’t good enough. But then I think, how can I be good enough when I’m up against a barrister?” This is a damning indictment of a seriously underfunded and broken system.

Failure to provide professional legal support in complex family law cases turns all parties into victims of a failed system, there is no justice for mothers, fathers and especially the children involved, setting them up for mental health issues that may negatively impact the rest of their lives.

Whilst exact figures are hard to come by, some campaign groups, such as Fathers 4 Justice (F4J), and Parents Against Parental Alienation (PAPA) have highlighted the dangers of fathers and mothers who are forced to be Litigants in Person, on occasion facing abusers in Court and dealing with complex legal matters they are ill-equipped to manage effectively.

Measuring the true scale of suicides linked to family court outcomes is extremely difficult, as the majority of people who take their own lives leave no note or clear explanation. Much of the evidence comes through anecdotal reports from families, campaign groups, and local media. Within parental alienation groups alone, at least 45 cases have been reported this year, and the Samaritans previously estimated that as many as 800 male suicides annually could be connected to family court decisions, especially over access to children. That estimate has since been quietly dropped, reflecting a wider institutional reluctance to acknowledge or research this emotional and difficult area. While precise data is lacking, the persistence of such claims highlights a grave gap in understanding, and the refusal to properly measure the problem is itself a national disgrace. Every life lost in this way is a personal tragedy, and most are preventable.

The historical development of the legal aid system indicates that the public’s right to justice is not merely a legal formality but a necessary avenue for the protection of individual rights against state power (Hemsworth, 2021). The ongoing underfunding poses significant risks not only to the integrity of the legal system but also to social equity itself, highlighting a disconnect between policy intentions and the availability of essential services (Garoupa & Stephen, 2004) (Boylan et al., 2016). The current state of the legal aid system, characterised by inadequate resources and sparse coverage, fundamentally challenges the notion of justice as a right rather than a privilege, calling into question the effectiveness of the UK’s commitment to equitable legal support (Okoro, 2022) (Baker & Barrow, 2006).

Before LASPO, in 2013, there were over 2,500 organisations providing civil legal aid, a number that dropped to about 1,800 by June 2025, with The Law Society reporting that by October 2024, only 1,236 firms held civil legal aid contracts. In 2013, around 1000 law firms offered legal aid support in criminal case law, that figure has not dropped to less than 700 in 2025.

Thus, whilst the UK legal aid system historically emerged from noble intentions to ensure access to justice, decades of underfunding and policy shifts have eroded its effectiveness. This situation persists despite evidence of the social and economic benefits that adequate legal aid provision can offer, underscoring a critical need for systemic reforms within this essential component of public service (Teufel et al., 2021) (Okoro, 2022) (Baker & Barrow, 2006).

Restorative Justice

In recent decades, the introduction of restorative justice principles has signalled significant evolution within the criminal justice framework in England and Wales. These principles advocate for collaboration involving victims, offenders, and communities.

Programs such as Youth Offender Panels illustrate the shift toward integrating restorative justice practices, facilitating dialogue between victims and offenders, which fosters a broader understanding of crime’s impact (Bouffard et al., 2016).

The collaborative nature of restorative justice seeks to amend traditional practices, emphasising rehabilitation over punishment and promoting a holistic view of justice prioritising societal reintegration (Bouffard et al., 2016).The effectiveness of restorative justice (RJ) in the UK since its introduction has been widely debated, with a growing body of literature analysing its impact on both recidivism rates and victim satisfaction. Restorative justice, which emphasises repairing harm through dialogue between victims and offenders, has been implemented in various contexts, particularly in youth offending and community justice settings. Overall, findings indicate a positive reception, though outcomes have been mixed and contingent upon specific implementation contexts.

One of the key strengths of restorative justice is its ability to address victims’ needs in a more personalised manner than traditional punitive systems. Studies have shown that RJ practices can enhance victims’ perceptions of satisfaction and empowerment by involving them in the justice process and allowing them to express their needs directly to offenders (Hobson et al., 2022) (Hoyle & Rosenblatt, 2015). Research by Hobson et al. emphasises the renewed integration of restorative approaches into UK policing, particularly in youth crime scenarios, suggesting that restorative practices can be effective tools for reducing youth violence and enhancing community relations (Hobson et al., 2022).

In terms of recidivism, empirical studies have produced varied results. Some meta-analyses indicate that restorative justice can significantly reduce recidivism rates among participants, emphasising its potential to promote behavioural changes in offenders (Latimer et al., 20050) (Lin et al., 2023). These findings suggest that when offenders engage in restorative justice practices, where they are held accountable and can see the impact of their actions on victims, they are less likely to reoffend compared to those who undergo traditional punitive measures.

However, challenges remain in achieving consistent outcomes across diverse populations. For instance, Willis and Hoyle found that offenders from disadvantaged backgrounds may not respond as positively to restorative justice initiatives and might perceive the processes as insincere if facilitators harbour biases against them (Willis & Hoyle, 2019). This reflection on “street culture” highlights how systemic issues can influence the reception of restorative justice among different demographic groups, potentially increasing the likelihood of recidivism when processes are misaligned with participants’ backgrounds.

Critics of restorative justice caution against its application in cases involving serious crimes, particularly domestic violence. Behrens’s work suggests that while restorative justice offers many benefits in community reconnections, it also poses substantial risks when victims may feel pressured to reconcile with offenders due to the restorative process’s nature, which can undermine their safety and autonomy (Behrens, 2005). This raises critical questions about the appropriateness of restorative justice for specific offenses and the necessity of careful implementation that prioritises victim safety.

Furthermore, the integration of restorative justice within the existing justice framework must consider the complexity of its goals. Walklate’s examination emphasises the importance of critical evaluation and adaptation of restorative practices over time to avoid repeating past mistakes that led to ineffective applications (Walklate, 2005). Surface level implementations that do not consider the unique contexts of offenders and victims may result in merely replicating traditional punitive outcomes rather than genuinely offering restorative solutions.

Overall, while there are promising signs regarding the effectiveness of restorative justice in fostering healing for victims and reducing recidivism in certain cases, the landscape is inconsistent and shaped by various factors including the nature of the offense, socio-economic background, and the implementation fidelity of restorative justice practices. Continuous evaluation and adaptation, alongside careful consideration of contexts and participant backgrounds, are advised to enhance the effectiveness of restorative justice within the UK justice system.

Restorative justice holds significant potential for addressing the needs of victims and promoting rehabilitation among offenders. Nevertheless, the evidence indicates that its effectiveness is mediated by several factors, necessitating ongoing research and refinement of these practices to maximize their positive impacts while minimising risks and drawbacks.

The Crown Prosecution Service

The establishment of the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) in the UK in 1986 was, in part, a response to several high-profile miscarriages of justice rooted in police misconduct. These incidents underscored systemic issues within the criminal justice system that highlighted the need for an independent prosecutorial agency.

One seminal case that exemplifies the extent of miscarriages spurred by police misconduct involved the wrongful conviction of the Birmingham Six. This group of six Irish men was convicted of carrying out pub bombings in Birmingham in 1974, which resulted in the deaths of 21 people. Their conviction was primarily based on coerced confessions and flawed forensic evidence. After years of campaigning, their convictions were quashed in 1991 when fresh evidence indicated that police had withheld critical information that could have exonerated them (Eisenberg et al., 2019). Such publicised failures instilled a sense of distrust in the criminal justice system and contributed to widespread calls for reform.

Another significant case that catalysed the creation of the CPS was the miscarriage related to the Guildford Four. Like the Birmingham Six, the Guildford Four were wrongly convicted based on police malpractice, including the fabrication of evidence and witness intimidation. They were imprisoned for 15 years before their convictions were overturned (Pflueger et al., 2015). The public outcry over such cases highlighted the urgent need for an independent body that could evaluate evidence objectively, free from potential biases rooted in police culture and conduct.

Additionally, the wrongful convictions in the 1980s’ not only exposed police misconduct but also pointed out shortcomings in the prosecutorial system, emphasising the necessity for a more scrutinised approach to how cases were managed. The CPS aimed to address these issues by ensuring that the prosecution process relied on legal professionals independent of the police force. This shift was essential for managing conflicts of interest, as prosecutors would henceforth evaluate cases based on evidence without undue influence from police departments, which could have vested interests in maintaining convictions previously secured under questionable circumstances (Edberg et al., 2022).

The systemic nature of these miscarriages of justice echoed the failures of police practices, which included a lack of accountability and oversight. Studies indicated that such failures often stemmed from ingrained institutional practices that prioritized securing convictions over seeking justice (Shishane et al., 2023). The CPS was tasked with rectifying this by fostering a culture of diligence and fairness, allowing for thorough and impartial case assessments.

Whilst the CPS was born out of a clear recognition that the failures attributable to police misconduct, exemplified through cases like those of the Birmingham Six and Guildford Four, necessitated an independent prosecutorial body. This aim was not solely to prevent future miscarriages of justice but also to restore public confidence in the criminal justice system as a whole. The establishment of the CPS signified a pivotal reform in ensuring that prosecutorial responsibility and police conduct were held to a higher standard, marking a critical shift in the UK’s approach to justice.

Prior to the CPS, decisions to prosecute were often made solely by police officers, leading to potential bias and inconsistency (Mou, 2017). The formation of the CPS marked a significant shift towards a more structured and impartial approach, allowing prosecutors to operate independently while collaborating with law enforcement (Swift, 2020).

The establishment of the CPS also aimed to meet public expectations for justice and accountability. Throughout the late 20th century, calls for increased transparency and fairness in the legal system intensified, particularly following media coverage of perceived injustices. The CPS was intended to enhance public trust by ensuring prosecution decisions are made based on objective criteria rather than subjective police judgment.

This intention reflects the principle that the legal system should prioritise the public interest, necessitating an independent body to evaluate evidence and make prosecution decisions (Hughes, 2014). The CPS is funded through government allocations, indicating its role as a critical component of the public sector criminal justice system. This funding aligns with operational needs, including personnel salaries and resources for effective legal proceedings.

Over the years, funding has adapted to address challenges within the criminal justice system, striving to maintain high service standards amidst shifting crime rates and public policy (“Collaborative Community Approaches to Addressing Serious Violence”, 2023).

Since its inception, the CPS has faced financial pressures, contributing to discussions about budget constraints on prosecutorial discretion and the efficacy of prosecutorial services (Detotto & McCannon, 2016).Throughout its history, the CPS has played significant roles in landmark prosecutions and legal reforms, notably in domestic violence and sexual offenses, where it developed specific guidelines for sensitive approaches (Madoc‐Jones et al., 2015).

Furthermore, the CPS has been involved in addressing new crime types, such as human trafficking, demonstrating its adaptability in a changing legal landscape (Atkinson & Hamilton‐Smith, 2020).

The CPS has also scrutinised prosecutorial decisions related to public interest and evidential requirements in complex cases like gross negligence manslaughter, underscoring its role in upholding justice (Swift, 2020). In conjunction with their prosecutorial responsibilities, the CPS focuses on training and capacity building for prosecutors, essential for adapting to the evolving landscape of criminal law and societal expectations. This mandatory training includes updates on legal precedents and ethical conduct, highlighting the need for legal expertise and a commitment to public service (Gupta et al., 2018). Moreover, administrative changes, such as implementing activity based planning systems, have been adopted to maximise efficiency and ensure judicious use of CPS resources in responding to cases (Liu et al., 2008).

Despite the initial intention for independence, recent critiques suggest that the boundary between the CPS and police has significantly narrowed over the years. Evidence shows an increasing collaboration between these two entities, often termed as “convergence,” where the prosecutorial decisions made by the CPS are heavily influenced by police investigations and their outcomes (Shishane et al., 2023). This challenging dynamic can potentially lead to issues where the CPS acts more as an extension of police efforts rather than as a separate, critically evaluative body, which raises concerns about prosecutorial integrity and independence (Li et al., 2015).

Reports have indicated troubling patterns in which the relationship between police and the CPS can lead to biases in prosecutorial judgment processes. For instance, systemic issues like disclosure failures have been highlighted, which point to police misconduct undermining the prosecutorial function, an ironic twist given the CPS’s origin (Shepherd et al., 2016). This situation is exacerbated by the fact that, as research has indicated, a significant percentage of wrongful convictions still stem from witness perjury and police misconduct, calling into question whether the independence the CPS was meant to embody has indeed been compromised (Mpofu et al., 2016).

Furthermore, the CPS has faced significant budgetary constraints that can impact its operational independence, leading to reliance on police led investigations and evidence, thus jeopardising its ability to function impartially (Ahidjo, 2024). Specific incidents, including low prosecution rates for serious offenses such as sexual assaults, reflect how systemic issues hinder the effectiveness of the CPS and suggest a disparity between intended prosecutorial independence and actual practice (Bird & Grattet, 2015). In recent years, the CPS has faced scrutiny regarding its procedures and the accountability of prosecutors, particularly in sensitive cases, which highlights the necessity for clear communication about prosecutorial discretion (Swift, 2020).

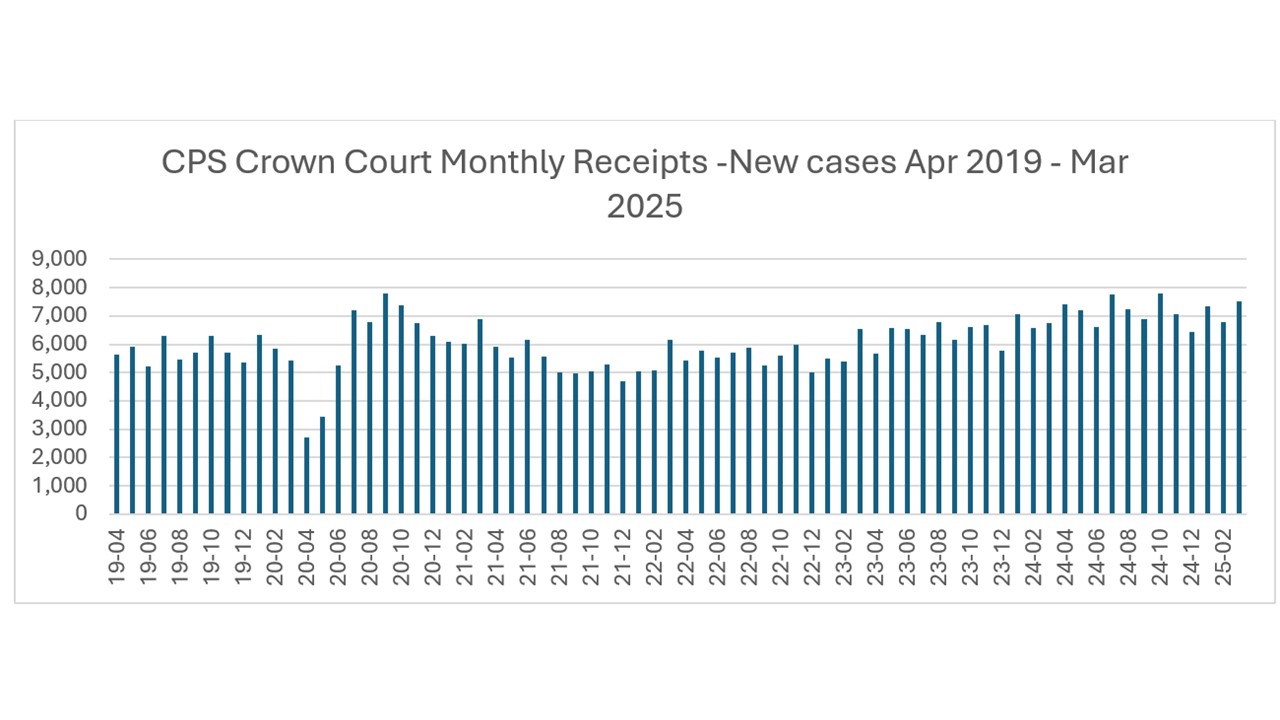

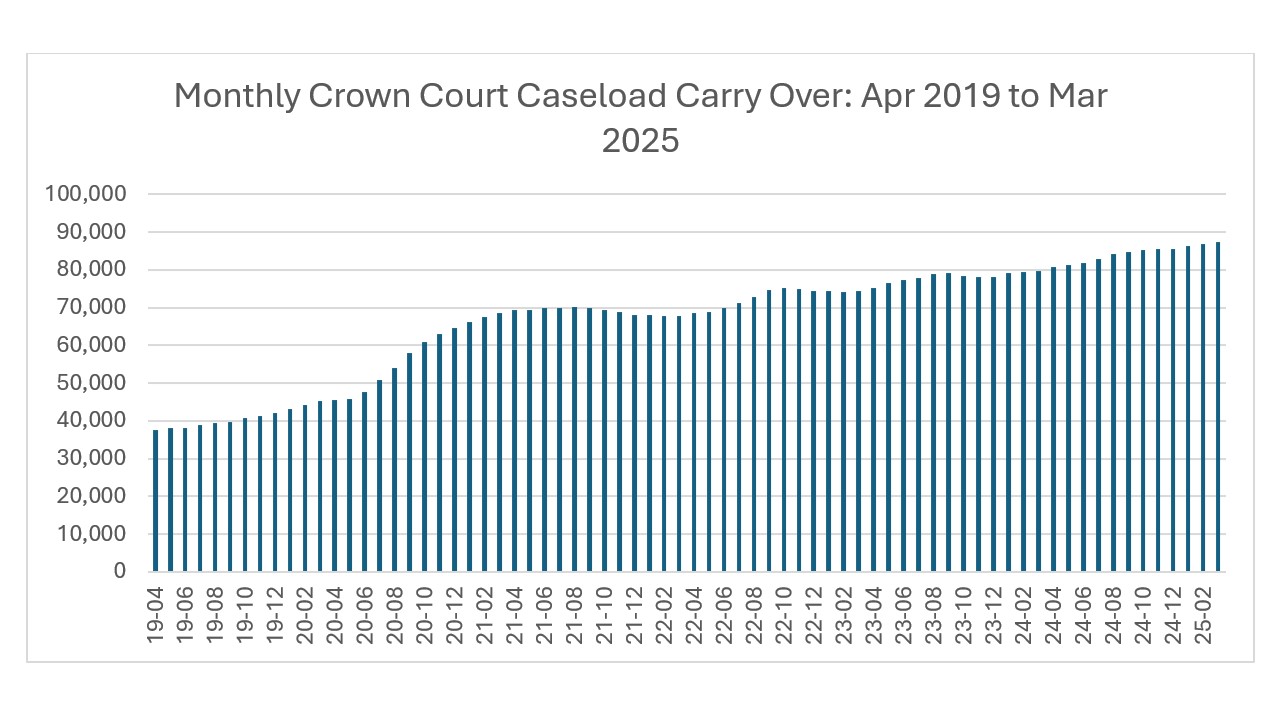

The data in the following two graphs was generated from the CPS Court Caseload Tables Q4 24-25 and is available to download from the CPS website.

The caseload of the CPS has been steadily increasing, but their funding has not been allowed to grow to absorb this increased workload, on top of this, the backlog of cases, as can be shown in the bottom graph, is increasing at an ever growing rate. This should be a central concern. A large number of defendants in Crown Court cases may be on remand, held in prisons until their case is heard, and based on current statistics, around 20-25% of those people are innocent of any crime, but they may be held in detention for up to 3 years before their case is either thrown out, stopped by the CPS or they are simply found not guilty.

As of the latest available data from December 2024, there were 17,023 people held on remand in England and Wales, which was a record high for at least 50 years and represented ~20% of the total prison population. This figure reflects the increasing number of people held in custody while awaiting trial, driven largely by backlogs in the criminal courts following the COVID-19 pandemic that have still not been resolved due to a lack of financial and human resources within the Criminal Justice System and especially the CPS.

In recent months, as of August 2025, there are increasing concerns that many are pleading Guilty to crimes they have not committed because their probable sentence is shorter than the time on remand. This is damning indictment of a failing system.

Changes in public attitudes toward justice and equity have prompted ongoing discussions about the limitations of current prosecutorial frameworks, pushing the CPS to continuously review its strategies to remain relevant and effective amid emerging legal challenges (Detotto & McCannon, 2020).

Rape and Sexual Offences – The Emotional Knife Edge in need of Reform – but how!

The latest CPS data on rape prosecutions lays bare a system in deep crisis. In 2024/25, survivors waited on average more than five months for a charging decision, with cases involving early investigative advice taking well over a year. Fewer than four in ten consultations were completed within the CPS’s own 28-day benchmark. Conviction rates fell below 60% overall and barely exceeded 50% in adult rape cases, a stark contrast with conviction rates of over 80% across all crimes.

These figures are not dry metrics: they represent lives in limbo. Survivors left waiting in uncertainty often withdraw, unable to endure the stress of months or years of delay. At the same time, defendants, many of whom will ultimately not be convicted, may spend more than a year under suspicion, reputations ruined, jobs lost, and families fractured. In rape cases, the system too often delivers neither protection for victims nor fairness for defendants.

Where responsibility lies is far from clear. Delays may be caused by over-stretched police investigations, the complexity of digital and forensic evidence, slow CPS decision-making, victims withdrawing support, or procedural bottlenecks within the courts. Each factor contributes to a vicious cycle of attrition and mistrust. Reform is desperately needed, but it must tread carefully. Lowering evidential thresholds risks false convictions and miscarriages of justice; failing to act condemns thousands of survivors to silence and despair.

This is the knife edge on which rape and sexual offence prosecutions now rest. Any meaningful reform must balance compassion with rigour, fairness with certainty, and above all the fundamental principle that justice must be both swift and sure.

Thus, the CPS has undergone a significant evolution since its establishment in 1986. Its intended independent nature, funded primarily by government allocations, reflects its operational effectiveness while navigating the complexities of the criminal justice system. The CPS continues to address modern challenges within the legal framework, particularly regarding prosecutorial discretion, victim support, and community collaboration in service delivery. However, is the CPS past its sell by date. Has it reached the end of the road under the current framework it is required to work within. This is a fundamental question that needs to be properly addressed if these islands are to maintain Justice for all, equally, regardless of the allegations and their social standing.

The Electronic Evidence System in Courts and the CPS

The reliance on electronic evidence within the UK’s judicial framework has come under scrutiny following various reports illuminating the operational flaws present in the systems employed by the Courts and the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS). These deficiencies primarily manifest in the withholding and mishandling of statements and other vital pieces of evidence, which can have extensive implications on the efficiency of justice and the rights of the accused. The functioning and governance of electronic evidence involve complex legal principles intertwined with the conduct of trials, and scholars have debated the reliability and authenticity of such evidence within the UK legal context.

A pivotal aspect of the current discourse is the principle of admissibility, which governs whether electronic evidence may be presented in court. The UK’s framework surrounding electronic evidence is dictated by the Civil Evidence Act 1995 (CEA 1995) and the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE 1984), which establish guidelines for the acceptable forms of evidence in civil and criminal cases, respectively. These pieces of legislation aim to ensure that all evidence presented is both relevant and reliable. However, contemporary findings suggest that systemic failures frequently lead to procedural breaches, undermining the credibility of the justice system. Mohamad (2019) discusses how issues of authenticity and admissibility can negatively impact the integrity of electronic evidence in court proceedings, aligning with various legal analyses that highlight shortcomings in technical regulations governing electronic submissions (Mohamad, 2019).

Significantly, the shortcomings of the electronic evidence systems raise questions about prosecutorial conduct. Instances of prosecutor misconduct, such as the deliberate withholding of exculpatory evidence, contravene the ethical obligations of fairness and justice that underpin the legal system. Bettens and Redlich assert that such misconduct violates fundamental rights and perpetuates wrongful convictions by obscuring essential pieces of evidence that could exonerate the innocent (Bettens & Redlich, 2023). This highlights the broader ethical imperatives within the justice system, where the obligation to provide a fair trial is paramount, and any lapses in this regard may lead to irreversible consequences for defendants.

Further complicating the situation is the cumulative nature of evidential biases that manifest across the judicial process. Scholars note a worrying trend where the cumulative disadvantages faced by suspects, often exacerbated by lapses in disclosure, can lead to unjust outcomes, such as coerced confessions or misinterpretations of evidence (Scherr et al., 2020). The ramifications of such biases extend beyond individual cases; they pose a significant threat to public trust in the legal system, as individuals who perceive systemic failures may be less likely to engage with legal processes, thereby perpetuating crime cycles and the perception of inequity.

The intersection of technology and legal standards presents further challenges for prosecutions reliant on electronic evidence. As new forms of technology emerge within courtrooms, evidence sourced from advances in forensic analysis present challenges regarding reliability and oversight. Scrutiny surrounding forensic methodologies indicates a critical need for standardised practices to ensure evidential accuracy, especially concerning techniques like face matching technology, which can lead to misjudgements in identifying suspects (Moreton, 2020). Establishing reliable protocols would serve to reinforce the integrity of prosecutions, benefiting the judicial process and society’s confidence in the Criminal Justice system.

Moreover, the increasing digitisation of evidence repositories necessitates acknowledging the risks associated with data loss or corruption. In an environment where key pieces of evidence may inadvertently be lost or mismanaged, the prospects for fair trial rights become alarmingly tenuous. The importance of adhering to data management best practices within the police and CPS cannot be overstated, as this serves as a baseline to mitigate the risks of withholding evidence, thereby safeguarding the moral and ethical standards of justice in these Islands (Bettens & Redlich, 2023).

As UK courts embrace technological advancements, maintaining the integrity of electronic evidence systems becomes paramount. The observed failures highlight an urgent necessity for reform, derived not only from implementing more robust technological protocols but also requiring a cultural shift within prosecutorial practices that emphasise accountability and transparency. Key reforms would include clearer guidelines based on the ethical management of evidence, outreach efforts to educate legal professionals on recent technological necessities, and regular audits to ensure compliance (Mohamad, 2019).

A systematic examination of how evidence is collected, managed, and presented is essential to adhere to the established legal framework and affirm the commitment of the judicial system to uphold civil rights. The integrity of evidence is crucial if the courts are to maintain public confidence in their processes and judgments.

The systemic flaws within the electronic evidence systems utilised by the Courts and CPS present a compelling challenge to the integrity of the judicial process in the UK. These failures, notably in the form of evidence withholding and mishandling, underscore the necessity for systemic reform. Emphasising ethics, accountability, and transparency in relation to evidence management is essential to reaffirm public trust and ensure fair judicial outcomes.

Failure to address these issues reinforces existing disparities within the legal system and poses substantial risks to individual rights.

Public Prosecutor Office Alternative

There have been discussions advocating for the establishment of a dedicated prosecutors’ office, focusing specifically on criminal prosecution, as a potential alternative to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) in England and Wales. This call has emerged from various critiques of the current prosecutorial framework, particularly concerns regarding the independence and objectivity of CPS prosecutors.

One of the central arguments for creating a dedicated prosecutors’ office stems from the perceived lack of impartiality inherent in the CPS’s structure, which operates within a system where police and prosecution functions are intertwined. Critics argue that this overlap can lead to motivations driven by law enforcement objectives rather than an objective pursuit of justice (Lee, 2016; Mou, 2017). The independence of prosecution decisions is fundamental to ensuring that justice is served fairly and without bias; however, the current model is sometimes viewed as compromised by its ties to police investigations, which can influence prosecutorial decisions and foster distrust among the public regarding objectivity in sensitive cases (Lee, 2016) (Mou, 2017).

Calls for reform also emphasise the need for specialised resources and focus on specific crime categories, such as domestic violence or human trafficking, where victims often suffer due to systemic shortcomings in the existing prosecutorial approach (Atkinson & Hamilton‐Smith, 2020) (Burman & Brooks, 2018). Establishing a dedicated prosecutors’ office could enable targeted strategies and expertise in highly specialised areas, potentially leading to better outcomes for victims and a more thorough pursuit of justice in nuanced cases that require a specialised understanding of law and victim dynamics (Nichols & Heil, 2014). This argument aligns with observations regarding the differences in effectiveness when dedicated units address complex issues like human trafficking, where tailored resources and strategies have been shown to lead to greater success in prosecution and victim support (Atkinson & Hamilton‐Smith, 2020) (Nichols & Heil, 2014).

Moreover, advocates for a new prosecutors’ office posit that such an institution could foster greater accountability and transparency in prosecutorial practices. A stand-alone entity could facilitate clearer communication about prosecution decisions and enable public scrutiny and oversight that currently exists at a far lesser degree within the CPS framework. This could aim to mitigate public concerns that arise from the perceived discretion exercised by prosecutors under the CPS, which some argue is often influenced by prevailing political or institutional pressures (Cammiss & Cunningham, 2014).

In conclusion, while the CPS has played a critical role in the prosecution of crimes in England and Wales, there are ongoing calls for a dedicated prosecutors’ office. Advocates for such reform argue that this could enhance prosecutorial independence, specialise in addressing complex crime areas, and contribute to greater accountability and public trust. These arguments encapsulate a broader need for systemic changes within the criminal justice system to ensure fairness, effectiveness, and victim-centred responses in prosecutorial processes.

Public Defenders Office alternative to legal Aid in Criminal Cases.

In recent years, there have been discussions advocating for the establishment of public defenders’ offices to replace or supplement the existing legal aid system in criminal cases. These calls primarily arise from systemic concerns regarding the effectiveness and reliability of legal aid as it currently stands. Advocates argue that a dedicated public defenders’ office could enhance the quality of legal representation for indigent defendants, ensure greater accountability, and foster a more equitable criminal justice system.

One of the primary arguments for establishing a public defenders’ office revolves around the inadequacies of the existing legal aid system. Critics suggest that legal aid often suffers from chronic underfunding and resource constraints, leading to high caseloads for attorneys. This situation has been shown to undermine the quality of legal defence that defendants receive, particularly in complex cases where specialised legal knowledge is essential (Hanlon, 2018) (Gottlieb, 2021). Public defenders’ offices could be established with the specific goal of ensuring that all individuals facing criminal charges receive the robust legal representation they are entitled to under the law (Nunes, 2020).

Moreover, public defenders are typically experienced in navigating the criminal justice system and may be better positioned to advocate effectively for their clients compared to private advocates who may lack the same focus or experience in criminal defence (Linhorst et al., 2017). Establishing public defenders’ offices could delineate a clearer pathway for legal representation and effectively allocate resources, allowing for a higher standard of legal service that reflects the complexities involved in criminal cases (Berryessa, 2022).

Public opinion on this issue appears supportive, given the ongoing critiques of the legal aid system’s inadequacies and its perceived failure to meet the needs of vulnerable and marginalized communities. Evidence suggests that public defenders often handle the majority of indigent defence cases, highlighting the potential for a more structured and properly funded approach through official public defenders’ offices (Xie & Berryessa, 2024). Such an office could receive dedicated funding, prioritising the recruitment and training of skilled legal professionals whose primary responsibility is to uphold the rights of those who cannot afford legal counsel.

Another argument for establishing an office focused specifically on public defence includes the potential for better advocacy for marginalised populations, including clients with mental health issues (Linhorst et al., 2017). The targeted development of policies and approaches tailored to specific vulnerabilities could lead to more effective outcomes and resolutions in legal matters involving complex human rights implications. Public defenders’ offices might enhance the focus on mental health concerns by providing specialised support structures for these clients, thereby improving legal outcomes and helping to address the intersectionality of systemic injustice (Nisihara et al., 2017).

These discussions regarding the development of public defenders’ offices suggest an evolving perspective on the role of legal representation in promoting justice and fairness in the criminal justice system. By ensuring that dedicated public defenders are available to represent the most underserved populations effectively, advocates believe that systemic disparities in legal representation can be addressed more holistically. This shift could not only enhance individual cases but, more broadly, restore faith in a justice system perceived to be failing a significant portion of the population.

Finally, the calls for establishing dedicated public defenders’ offices promise an opportunity for reform that could address many of the shortcomings faced by the current legal aid system. By improving the quality of representation for indigent defendants and providing specialised resources, such offices could better fulfil the ethical and legal obligations of safeguarding justice, accountability, and equitable treatment within the criminal justice system.

The Prison System in the UK

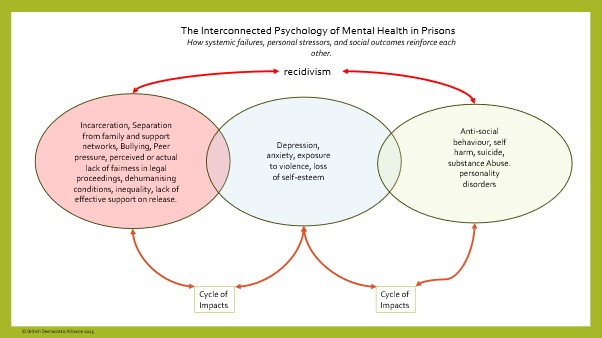

This diagram illustrates how imprisonment, mental health decline, and destructive behaviours form a reinforcing cycle. Incarceration and separation from support networks create psychological harm, which manifests as depression, anxiety, and loss of self-worth. These in turn feed into anti-social behaviour, self-harm, and substance abuse, driving recidivism and returning individuals back into the same system. Without meaningful intervention, prisons become not places of rehabilitation but engines of repeated harm, both for the individual and for society.

The British prison system has undergone considerable scrutiny and transformation since 1990, with critical discussions revolving around prison conditions, funding issues, rising suicide rates, overcrowding, and the efficacy of rehabilitation programmes. This response aims to synthesize the available research to provide a comprehensive view of the state of the United Kingdom’s prisons over the past three decades.

Prison Conditions and Overcrowding

Prison overcrowding has emerged as a significant problem in the UK, where facilities often operate beyond capacity. The issue was highlighted in a study illustrating that local and overcrowded prisons exhibit higher suicide rates, primarily due to their higher prisoner turnover rather than overcrowding itself having a direct correlation (Ginneken et al., 2017). This phenomenon accentuates the stressful environment and can exacerbate psychological distress among inmates. Generally, overcrowding in prisons is linked to larger systemic failures, such as reduced staffing levels and inadequate facilities, which create challenges for effective inmate management and rehabilitation (Ginneken et al., 2017) (Fazel & Seewald, 2012).

Moreover, overcrowded conditions often undermine the psychological well-being of prisoners. Faced with reduced personal space and privacy, inmates report heightened levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms, resulting in a grim statistical reality where suicide rates remain alarming (Hawton et al., 2014) (Senior et al., 2014). A systematic review has suggested troubling correlations between mental health issues and prison overcrowding, highlighting that prisoners in congested facilities show increased vulnerability to suicidal behaviour, particularly when institutional responses lack adequate mental health resources (Ginneken et al., 2017) (Fazel & Seewald, 2012).

Suicide Rates and Self-Harm

Since 1990, suicide rates within British prisons have been a growing concern, with various studies documenting alarming statistics. Research indicates persistent high rates of self-inflicted deaths, especially among younger male prisoners (Fazel & Benning, 2009) (Pratt et al., 2006). A longitudinal study noted that the highest standardised mortality ratio (SMR) for suicides is often found among the youngest inmate demographics, indicating a need for targeted mental health interventions for those aged 15 to 17 years Fazel & Benning (2009) (Pratt et al., 2006).

The stigma surrounding mental health within the prison environment hinders inmates from seeking help, contributing to sustained high rates of self-harm. Studies show substantial evidence that a significant number of prisoners experience severe mental health disorders, with one in seven suffering from depression or psychosis (Fazel & Seewald, 2012) (Senior et al., 2014). The lack of mental health resources in prisons exacerbates these conditions and leads to increased risky behaviours, including self-harm and suicidal ideation (Senior et al., 2014). The Prison Service’s response in recent years has involved implementing various suicide prevention strategies; however, these measures often lack effectiveness due to the pressing problems of overcrowding and inadequate staffing (Blaauw et al., 2005) (Nixon, 2022).

Funding Problems and Resource Allocation

Funding deficits within the prison system have had a detrimental impact on the quality of care provided to inmates. Over the last two decades, the financial constraints faced by the prison service have resulted in reduced access to mental health services, educational programmes, and rehabilitation opportunities (Senior et al., 2014). The shift of responsibilities for healthcare towards the National Health Service (NHS) was intended to improve mental health services in prisons; however, this transition was slower than necessary to address the immediate mental health crisis faced by inmates (Senior et al., 2014). Consequently, the lack of resources is often reflected in the high incidence of both self-harm and suicide among prisoners, indicating that mental health needs remain unaddressed.

In terms of education and rehabilitation programmes, there is a pressing need for investment in these areas to facilitate reintegration and reduce recidivism. Significant gaps in educational provision, which traditionally focus on basic literacy and vocational skills, leave many prisoners inadequately prepared to reintegrate into society post-release. Without this crucial support, the cycle of offending often continues, as reintegrating successfully into society becomes an uphill battle for released prisoners (Nixon, 2022).

Mental Health and Rehabilitation Schemes

The integration of mental health support within the prison infrastructure has been a focal point for reform in recent years. The introduction of ‘in-reach’ mental health services, analogous to community mental health team models, has been implemented to better address the psychiatric needs of prisoners (Senior et al., 2014). Such programmes aim to identify and manage prisoners who are at risk of suicide or self-harm actively. Nevertheless, challenges persist, as these initiatives often lack sufficient staffing and funding, resulting in inadequate care provision (Fazel & Seewald, 2012) (Senior et al., 2014).

Furthermore, studies indicate that peer support programmes have been beneficial in enabling inmates to discuss their mental health issues and learn coping strategies from one another. These initiatives promote a stigma-free environment and can facilitate healthier coping mechanisms among inmates (Nixon, 2022).

Despite these efforts, comprehensive rehabilitation remains hindered by socio-economic barriers faced by prisoner’s post release, including stigma, lack of employment opportunities, and social exclusion. These barriers contribute to a worrying trend of re-offending, suggesting that current rehabilitation efforts need to extend beyond the prison context to facilitate effective reintegration into society (Pratt et al., 2006) (Borrill et al., 2015).

The complexities of the British prison system unveil a multitude of interrelated issues involving overcrowding, mental health crises, inadequate funding, and ineffective rehabilitation programmes. A cohesive approach employing comprehensive mental health support, sufficient funding, and robust educational initiatives is essential to address the pressing issues within the system. Furthermore, improving conditions in terms of overcrowding is vital for enhancing inmates’ psychological well-being, ultimately reducing suicide and self-harm rates. As the UK continues to grapple with these challenges, ongoing research and policy reform will be crucial in formulating effective strategies to transform the current landscape of prisons and promote a more humane and rehabilitative approach.

A Comparison of Adult Male and Female Incarceration

The conditions, funding, mental health support, general health support, and rehabilitation pathways for adult male and female prisoners in England and Wales reveal significant disparities stemming from systemic gender related practices within prisons. This response synthesises evidence from existing literature to discuss these differences critically.

Conditions in Prison

Prison conditions in England and Wales differ markedly between male and female establishments. Female prisoners often face significant issues related to the physical environment, partly due to the smaller scale of women’s prisons, which can lead to overcrowding as they are not designed to handle surges in female prisoner populations. Male prisoners constitute the majority of the prison population, leading to a prioritisation of resources and facilities towards them, which can detrimentally affect the quality of conditions for female prisoners (Turner et al., 2021) (Woodall et al., 2021). Furthermore, reports indicate that women’s prisons are often placed at greater distances from family homes than male prisons, leading to barriers in familial contact that are critical for emotional support post-incarceration (Woodall et al., 2021).

Funding Disparities

Funding for health services within prisons in England and Wales reflects broader systemic inequalities. Given that approximately 96% of the prison population is male, health services have historically been tailored more specifically toward male needs, often sidelining women’s specific health requirements. For instance, women in prison frequently have unmet healthcare needs, particularly in mental health services, exacerbated by lower funding allocations that fail to consider gender-differentiated health issues (Carson‐Stevens et al., 2024) (Senior et al., 2014).

Mental Health Support

The mental health landscape within prisons presents stark contrasts between male and female prisoners. Studies show that female prisoners experience higher rates of mental health issues compared to their male counterparts, often originating from previous trauma Senior et al., 2014). Moreover, the prevalence of self-harm and suicide is notably higher among female inmates, with female prisoners being 20 times more likely to die by suicide compared to women in the general population (Hawton et al., 2014). In contrast, while male prison populations also exhibit high rates of mental illness and self-harm, the systemic response to these issues tends to differ due to historical practices that have focused on male-specific responses (Knight et al., 2017; Senior et al., 2014).

General Health Support

General health care in prisons, while crucial for all prisoners, is often inadequately managed due to the unique needs of the diverse prison population. In England and Wales, male prisoners are served by health services that, while comprehensive, reflect systemic inequalities as they are often more heavily resourced compared to those available to female inmates (Carson‐Stevens et al., 2024; Bartlett et al., 2014). Research suggests that women prisoners often have distinct health needs that are historically overlooked, leading to inadequate healthcare practices that fail to address physical health issues unique to women, such as reproductive health (Woodall et al., 2021; Bartlett et al., 2014).

Rehabilitation Opportunities

Rehabilitation pathways reveal additional disparities. Although both men and women face challenges, female prisoners are frequently offered fewer educational and vocational training programs than their male counterparts. This disparity can lead to reduced opportunities for rehabilitation and successful reintegration into society upon release, as women often occupy more vulnerable positions socioeconomically (Tomaszewska et al., 2022). Gender-responsive approaches in rehabilitation are advocated to cater to the needs of female prisoners effectively; however, implementation remains inconsistent across institutions (Tomaszewska et al., 2022).

In summary, the comparative analysis of conditions, funding, mental health support, general health support, and rehabilitation opportunities for adult male and female prisoners in England and Wales underscores significant inequalities. These disparities not only impact the quality of life and health outcomes for female prisoners but also highlight the necessity for systemic reforms that recognize and address gender-specific issues in the prison system.

The Probation Service

The probation service in the United Kingdom has undergone significant changes over the years, particularly in its operational structures, with a notable shift occurring before and after 2010. Prior to 2010, the probation service was primarily a public body that oversaw the rehabilitation of offenders, aiming to prevent reoffending through community based interventions. The service operated under the guidance of the National Offender Management Service (NOMS), which was established in 2004 to provide a coordinated approach to managing offenders in both community and custodial settings.

The probation service’s focus was on rehabilitation, community safety, and integrating offenders back into society by providing support such as housing, employment, and access to treatment programs (Burrell, 2022) (McKnight, 2009).

The privatisation of the probation service was prompted by a combination of ideological, economic, and operational factors. The influence of neoliberal policies, characterised by a preference for market-oriented solutions and public service reforms, significantly impacted the conceptualization and delivery of probation services.

Successive governments, particularly under New Labour and later Conservative led administrations, promoted the idea that introducing private sector efficiency into public services could enhance performance and accountability (Scourfield, 2015) (Senior, 2016) (Robinson et al., 2017).

The Transforming Rehabilitation agenda, launched in 2013 by then Justice Secretary Chris Grayling, aimed to expand the role of the private sector in managing low and medium risk offenders, emphasising the need for innovative solutions in a context of constrained public spending (Annison, 2018) (Raynor, 2012).

The extent of privatisation was substantial, with a significant portion of probation services being outsourced to private and voluntary sector providers. This marked a departure from the tradition of probation being a fully public service. The contracting out of services was intended to foster competition and drive efficiency; however, this shift encountered notable challenges and raised concerns about the implications for service quality, accountability, and the overall ethos of rehabilitation (Senior, 2016) (Robinson et al., 2017) (Fitzgibbon & Lea, 2014).

Critics argued that privatisation could lead to a focus on profitability over effective rehabilitation strategies, potentially compromising the service’s foundational objectives of supporting individuals in their reintegration into society (Senior, 2016) (Collett, 2013).

Managing this transition was fraught with difficulties. The implementation of Transforming Rehabilitation was marked by poorly defined roles and responsibilities, leading to operational fragmentation. There were high-profile failures, such as the collapse of contracts awarded to private firms, which were unable to meet expectations set forth by the government. Issues such as staff shortages, lack of experience among private contractors, and insufficient understanding of community rehabilitation needs culminated in significant disillusionment with the model (Robinson et al., 2017) (Annison, 2018) (Fitzgibbon & Lea, 2014).

The complexity of integrating disparate organisational cultures between the public and private sectors further complicated the landscape, raising questions regarding the legitimacy and efficacy of the new system (Annison, 2018) (Collett, 2013).

In assessing the success or failure of the privatisation initiative, it is clear that the transition was marked by more failures than successes. Anticipated improvements in offender management outcomes did not materialise uniformly or significantly; instead, reports indicated that certain services suffered from disjointed practices, with detrimental effects on public safety and offender rehabilitation (Robinson et al., 2017) (Fitzgibbon & Lea, 2014) (Farrall, 2005). The lack of consistent oversight and accountability mechanisms contributed to deteriorating confidence in the system, prompting severe criticism from public and professional bodies, and exacerbating calls for the reintegration of services into public management models (Burrell, 2022) (Robinson et al., 2017) (Fitzgibbon & Lea, 2014).

As of today, the probation service is experiencing another phase of change as it shifts towards reintegration under the auspices of the National Probation Service. This recent development aims to recover some of the operational integrity and mission driven focus that was believed to be compromised through privatisation. The current state of the probation service reflects an ongoing struggle to balance effective rehabilitation programs with the complexities introduced by the privatisation process and subsequent attempts to reform activities to better serve communities (Collett, 2013) (Fitzgibbon & Lea, 2014). A significant push has emerged to refocus on the values of accountability, human service, and the principles of community justice, creating discussions around purpose and practice in modern probation (Burrell, 2022) (Collett, 2013) (Farrall, 2005).

In summary, the evolution of the probation service in the UK prior to and following 2010 embodies a broader narrative about the challenges and consequences of public sector privatisation within a neoliberal framework. The philosophical shifts towards market-based reforms, combined with operational challenges associated with the resultant privatisation, have led to a contentious landscape for probation services. Meaningful reflection on this trajectory remains essential as the service seeks to redefine and realign its mission towards effective rehabilitation and community reintegration in the years to come.

This “playing with lives” approach by successive governments cannot be the way forward. Not only is it in the public interest that those who break societies laws are educated on the error of their ways in an efficient manner that mitigates a repeat of their offending, but public safety should never be compromised for sound bites in political debates and ideology.

The Privatisation of the Probation service was an abject failure and can n never be repeated.

Alternatives to Imprisonment

The effectiveness of incarceration as a deterrent to criminal behaviour has long been debated, with many researchers emphasising the limited success of prison in reducing recidivism. Alternatives to incarceration, including probation, community service, house arrest, and electronic monitoring, have been explored in various jurisdictions, highlighting varying degrees of effectiveness.

For instance, house arrest is a noncustodial alternative that serves to keep offenders within their homes while allowing them to maintain employment, thus reducing the financial and social disintegration often associated with incarceration. This option has been implemented in the U.S. with mixed results, demonstrating potential benefits in keeping offenders engaged in society while reinforcing accountability and reducing the burden on prison systems (Bird et al., 2022). Moreover, curfewed detention, which restricts individuals from leaving their homes during certain hours, has been shown to contribute positively to rehabilitation efforts by maintaining social ties and job stability (Bird et al., 2022).

Community service has also emerged as a prominent alternative, which allows offenders to contribute positively to society and has displayed a marked decrease in recidivism rates when compared to short custodial sentences. Research indicates that those engaged in community service exhibit lower reoffending rates than their incarcerated counterparts, thereby supporting the argument for community-based corrections as a viable option (Killias et al., 2010) (Moliné, 2009). Comparatively, probation, while often intended as a rehabilitative alternative, has been critiqued for acting as a “net-widener,” inadvertently increasing overall supervision instead of reducing incarceration rates (Phelps, 2016) (Gu et al., 2023).

The implementation of electronic monitoring, as distributed in countries like Norway, highlights another effective alternative. By using GPS to monitor the whereabouts of offenders, this approach aims to balance community safety with rehabilitation, allowing individuals to maintain a semblance of normalcy during their rehabilitation (Andersen et al., 2020). However, the addition of electronic monitoring can sometimes skew judicial discretion, potentially leading to harsher outcomes for offenders who might otherwise benefit from less stringent measures (Andersen et al., 2020).

In regard to the public perception of these alternatives, studies indicate a significant correlation between awareness of such programs and overall societal support for their implementation. An example was in the Czech Republic, increasing awareness of probation initiatives led to a more favourable general public opinion regarding noncustodial sentences, suggesting that educational campaigns could further promote alternatives to incarceration (Tomášek et al., 2022).

In conclusion, alternatives to incarceration, such as house arrest, curfewed detention, community service, and electronic monitoring, demonstrate significant potential for reducing recidivism while allowing individuals to retain essential social and economic ties. By further promoting and implementing these methods, the UK could lead a progressive transition away from reliance on prison, ultimately fostering a more rehabilitative rather than punitive approach to criminal behaviour.

Overview of the Criminal Justice System

The Criminal Justice system is integral to the safe functioning of society, no matter our type of governance, the public must have confidence in the system to operate effectively. However, the system must also work fairly, treat all equally, no matter what position within society they may hold, no matter if they are homeless and poor, or a billionaire, everyone has the same basic human right of being treated the equally.

What we see in this chapter is that the Criminal Justice system in the UK, at least, is failing, and it has been for many decades. Chronic underfunding of the Courts, Prison Service, Police, Probation, Education system and the almost complete lack of effective mental health provisions have left the country flailing in a strong wind like a flag with only one attachment point, and the entire nation suffers as a result.

Investment in the Criminal Justice System

Investing in the criminal justice system often faces public and governmental scepticism, particularly regarding its efficacy in reducing crime and recidivism. However, research illustrates that targeted interventions focusing on educational standards and mental health can significantly impact recidivism rates among offenders. This is particularly relevant in the context of the UK, where alternatives to custody could provide a more rehabilitative approach.

Addressing educational deficiencies and mental health needs within the offender population can have transformative effects. Research suggests a strong correlation between educational attainment and criminal behaviour, indicating that offenders with lower educational levels are at a greater risk of recidivism (Mandracchia & Morgan, 2011). When offenders engage in educational programs, they not only acquire skills essential for employment but also develop cognitive behavioural strategies that can alter antisocial thinking patterns (Mandracchia & Morgan, 2010). For instance, cognitive behavioural interventions tailored to address criminal thinking have shown promise in reducing recidivism for individuals with prior convictions (Mandracchia & Morgan, 2010) (Hatchett et al., 2015).

Mental health interventions are paramount for reducing recidivism, as a significant proportion of offenders present with untreated mental health issues. Studies show that individuals with mental disorders are more likely to reoffend if their conditions are not adequately addressed (Payne et al., 2020) (Chitsabesan et al., 2006). In particular, programming that includes mental health assessments and subsequent therapeutic interventions can serve as effective preventive measures against recidivism (Yampolskaya & Chuang, 2012). Programs that integrate mental health care with probation supervision, as seen in successful models from international jurisdictions, could inform best practices for the UK system (Abracen et al., 2015) (Broner et al., 2004). Common mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety, negatively affect the prospects of rehabilitation, thereby highlighting the need for early intervention and ongoing support (Louden & Skeem, 2013).

Moreover, implementing alternatives to custody, such as house arrest or curfewed detention, can keep individuals within the community while ensuring compliance and promoting accountability (Bird et al., 2022). This approach allows offenders to maintain employment and engage with their families and communities, factors known to correlate with lower recidivism rates (Rijo et al., 2016). Such community based alternatives, when combined with effective educational and therapeutic programs, can lead to significant improvements in public safety and social cohesion (Yampolskaya & Chuang, 2012).

Furthermore, enhancing public awareness and perception of alternative sentencing options can engender broader societal support for reform. Research from various countries highlights the importance of public support in the successful implementation of rehabilitation services (Tomášek et al., 2022). Educational efforts aimed at the public might foster a more rehabilitative rather than punitive mindset, which is essential for the long-term success of criminal justice reforms in the UK (Ahidjo, 2024).

In conclusion, strategically investing in educational programs and mental health services for offenders, coupled with community-based alternatives to incarceration, promises to enhance rehabilitation outcomes and lower recidivism rates. By focusing on these dimensions, the UK’s criminal justice system can pivot towards a more effective, humane approach that acknowledges the complexities of criminal behaviour and the potential for rehabilitation.

How Can We Improve the Criminal Justice System?

The need to improve the success rate of the UK’s Criminal Justice System (CJS) regarding the prosecution of crimes, especially sexual offenses, and the rehabilitation of offenders to reduce recidivism is critical. A multidimensional approach is required, addressing systemic issues that currently hinder effective justice processes and contribute to high recidivism rates.

One significant concern is the current treatment of victims within the CJS, particularly for sexual offenses. Studies indicate that the experience of victims significantly impacts their engagement with the system and their desire for justice. Implementing victim centred approaches could help bridge the “justice gap” often experienced by survivors of sexual violence. For instance, initiatives that facilitate an active role for victims in the criminal process can enhance their satisfaction and perception of justice, which is vital for encouraging reporting and cooperation with law enforcement (Carroll, 2022). Additionally, improving the response from criminal justice professionals to victims, ensuring they feel believed and supported, is essential (Taylor-Dunn & Erol, 2022). Combining victim support with training for police and judicial staff about sensitivity can help foster a better overall experience for those seeking justice.

Regarding prosecutions, evidence suggests that implementing clear frameworks for police practices, such as the use of technologies like facial recognition, needs careful regulation to prevent misuse and ensure they aid in achieving justice effectively. Clear regulations can help police make informed decisions on using these technologies, balancing the need for effective policing with the rights of individuals (Ritchie et al., 2021). This legislative clarity could pave the way for more consistent prosecutorial outcomes and improved public trust in the justice process.

Furthermore, the rehabilitation aspect of the CJS is equally imperative in addressing recidivism. Evidence suggests that restorative justice programs can significantly reduce reoffending rates as they focus on rehabilitation and accountability rather than solely punitive measures (Ahidjo, 2024) (Priyana et al., 2023). Participants in such programs often report greater satisfaction with their justice experience and lower rates of recidivism compared to those who went through traditional punitive processes. Developing more robust restorative practices could lead to a system that not only addresses past wrongs but also focuses on healing and reintegration.

To further enhance rehabilitation, introducing personalised interventions tailored to the needs of offenders has shown promise in social care contexts and can be adapted for use within the CJS. The shift towards a “personalisation” model in social care highlights the potential for similar reforms in criminal justice, addressing individuals’ specific needs rather than applying a one size fits all approach (Fox et al., 2013). Mentoring programs that provide support at various stages of the justice process can also significantly aid rehabilitation efforts, particularly for marginalised groups (Hucklesby & Wincup, 2014).